Life, Death, Memory, Fate, Loss

Christian Boltanski

The artist’s explorations of emotion wrought by the Holocaust and the horrors of war profoundly resonate today more than ever

by Rochelle Steiner

Photo: Rebecca Fanuelle Courtesy Fonds De Dotation Christian Boltanski And Marian Goodman Gallery

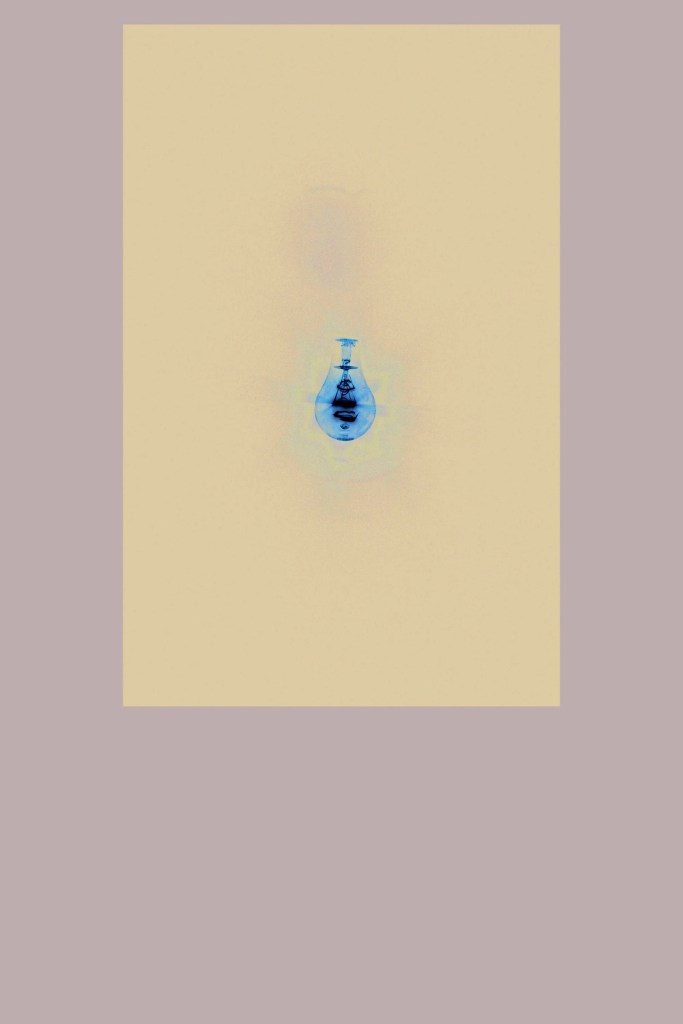

For more than 50 years until his passing in July 2021, artist Christian Boltanski was preoccupied with the most profound and challenging themes, both personal and collective. Life, death, memory, fate, loss, the Holocaust and the atrocities of war are subjects that consistently drove his creative output. It is difficult not to draw parallels between his haunting imagery and conditions today. War, genocide, migration, deportation, the search for asylum and exponential suffering experienced and witnessed across the world are all called to mind by his art.

Christian Libert. Boltanski was born in Paris in September 1944, shortly after the city was liberated from Nazi occupation, accounting for his middle name. His own origin story is at the heart of his work. According to the artist and his family lore, during the occupation in France, his parents-to-be staged an argument, giving rise to the belief that his father had abandoned the family. His Roman Catholic mother perpetuated this narrative, while his Jewish father hid under the floorboards of their home. On one of his father’s rare ventures out of hiding, Christian was conceived. The re-telling of this and other accounts as well as a childhood marked by the aftermath of the Holocaust and World War II were catalysts in Boltanski’s artistic career.

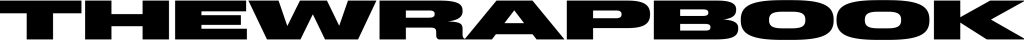

Beginning first in painting and then utilizing photographs and objects to create dramatic sculptural installations, he developed what became his haunting art. Comprising images, found materials, lights and sounds, his work is both disturbing and riveting in equal measure. Abundant are headshots from newspaper obituaries, family albums, postcards, police registries and other picture sources. They are typically manipulated through cropping, shading, enlarging, re-photography and other distortions, resulting in generalized rather than identifiable facial features. A sense of age, gender and time period can often be deduced, but these images are not presented as portraits of individual people. Rather, through artful visual storytelling, Boltanski conveys unknown histories that hover between reality and fiction.

Courtesy Studio Christian Boltanski And Marian Goodman Gallery

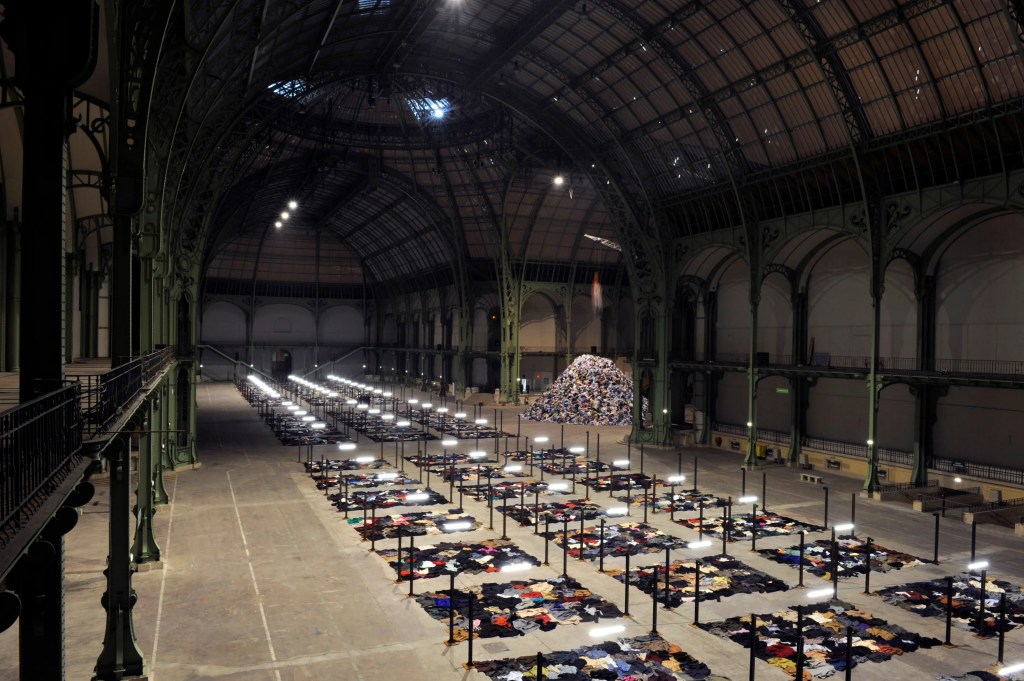

He also regularly incorporated mementos, clothing and other personal items into sculptural installations, resulting in remembrances of and memorials to lives lost. In an enormous 2010 installation “Personnes” at the Grand Palais in Paris (recreated later that year at the Park Avenue Armory in New York as “No Man’s Land”), the artist filled the space with more than 50 tons of used clothing, grouped in rectangular plots across the floor. The space was punctuated by a 25-foot-tall mound of garments piled high, over which a mechanical arm suspended from a crane repeatedly picked up, released and scattered sweaters, pants, jackets, dresses and the like, each item suggestive of a body. Boltanski described the act of selection from the multitudes as “a metaphor of chance”—referencing fate or “the finger of God.” In both Paris and New York, the installations were accompanied by soundtracks of thousands of human heartbeats, part of another project by the artist began in 2008 to record and archive heartbeats worldwide. (They are permanently archived in the artist’s project “Les Archives du Coeur” at Benesse Art Site Naoshima in Japan, actively added to by visitors.)

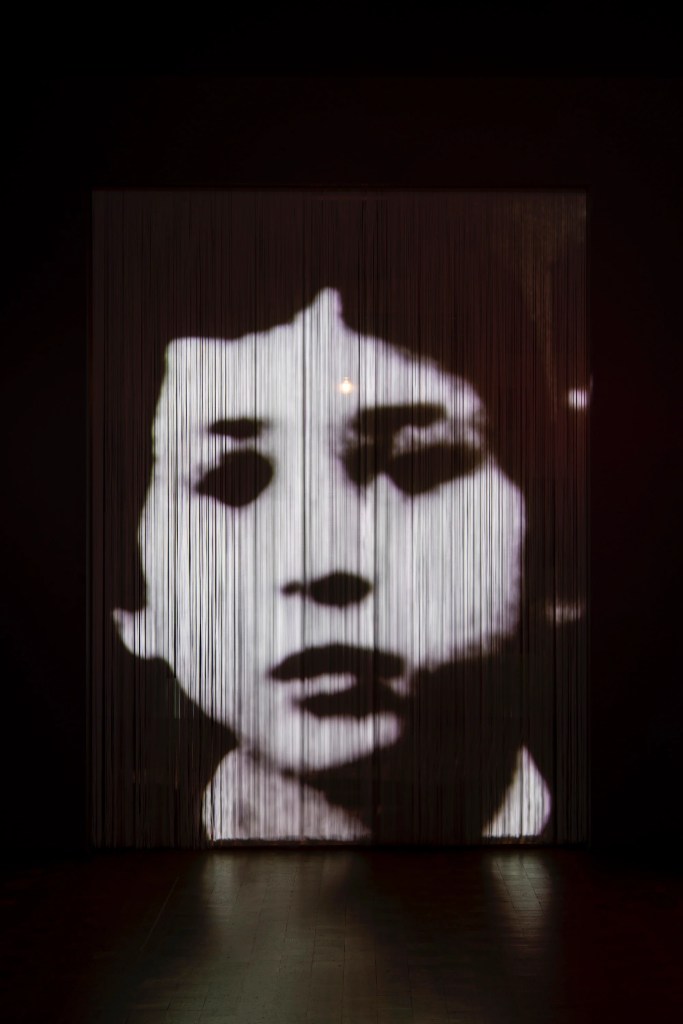

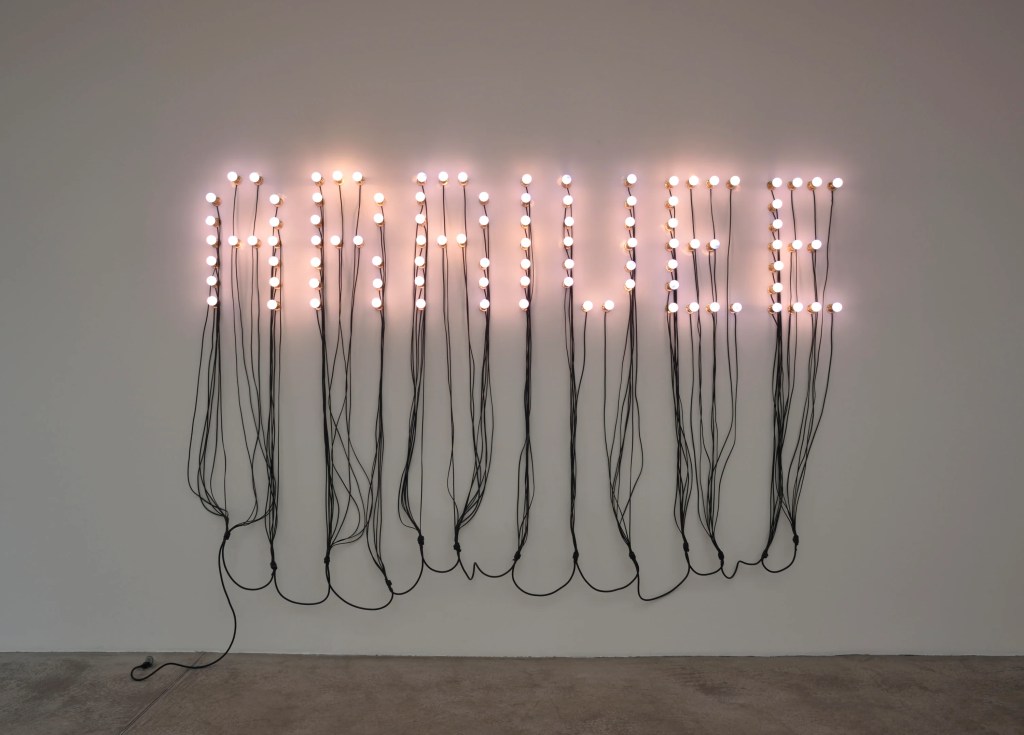

Most of Boltanski’s installations are darkened, with light emanating from bare bulbs or fixtures that suggest surveillance, interrogation or truth-seeking with varying degrees of intensity. At the same time, the haunting light, suggestive of votives on altars or Jewish Yahrzeit candles used to mark the anniversary of one’s death, also brings forth religious undertones. Consistently and dramatically, Boltanski mined life and loss to create ghostly, emotional and immersive installations. Unfortunately, and sadly, the insurmountable processes of remembering, grieving, memorializing and marking time at the center of his work are again and now as resonant as ever.

Photo: Rebecca Fanuele Courtesy Studio Christian Boltanski And Marian Goodman Gallery

Photo: Didier Plowy, Courtesy Of The Fonds De Dotation Christian Boltanski And Marian Goodman Gallery